A rarely-seen drawing of The Three Graces by Raphael offers a fascinating glimpse into Renaissance ideas about nudity, modesty, shame, and artistic genius. Featured in Drawing the Italian Renaissance at The King’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, this exhibition showcases over 150 fragile chalk, metalpoint, and ink drawings from 1450 to 1600. It is the largest exhibition of its kind ever held in the UK, with more than 30 pieces displayed publicly for the first time.

A Celebration of Renaissance Art

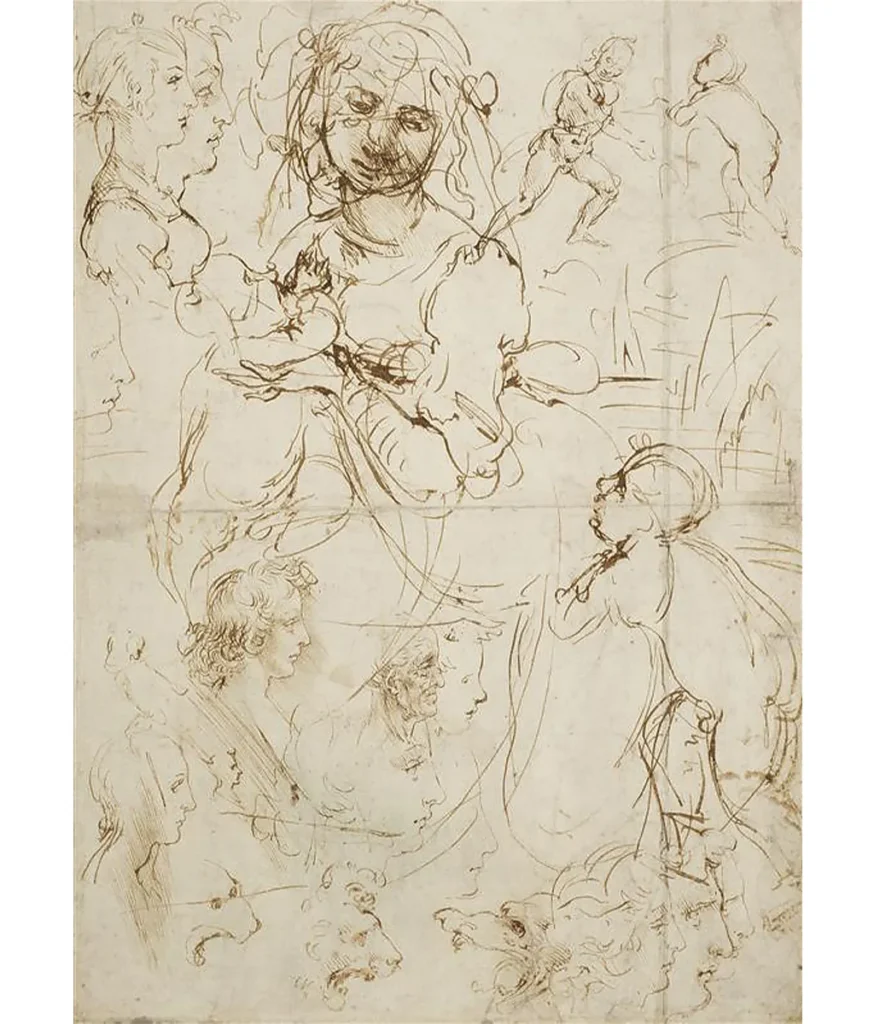

The collection includes works by iconic figures like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Titian. These drawings, often preparatory studies for larger paintings, began to be valued as standalone artworks during the Renaissance. Among the exhibition’s curiosities are depictions of a wandering lobster and a sturdy ostrich, but it’s the rare female nudes—outnumbered three-to-one by male figures—that challenge societal and artistic norms of the period.

Male Bodies and Divine Perfection

As historian Maya Corry explained on BBC Radio 4, Renaissance art prioritized the male form, considered the image of divine perfection in a Christian society. Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man exemplifies this ideal. Practical limitations also contributed to the rarity of female nudes: male-dominated workshops and societal norms made it inappropriate for women to model nude, leading artists like Michelangelo to rely on male models, often resulting in distorted female depictions.

Raphael’s Revolutionary Approach

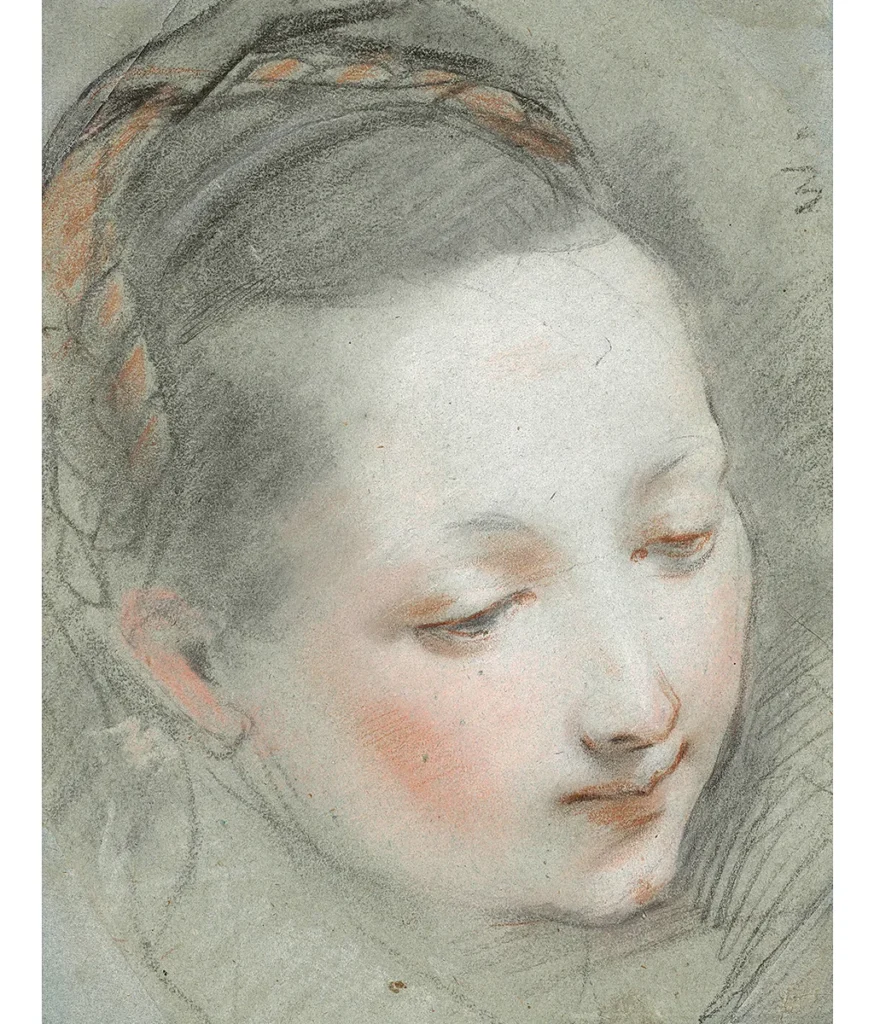

Raphael, however, broke with tradition by using real-life female models. His pragmatic and innovative approach is evident in his drawings, where he experimented with pose, proportion, and movement. In The Three Graces (c. 1517–18), a red chalk drawing with metalpoint underdrawing, Raphael captured a single model in three poses. This study was pivotal in crafting the exuberant fresco The Wedding Feast of Cupid and Psyche, where the Graces anoint the newlyweds.

The unclothed female form was not just an artistic challenge but also a scientific pursuit, echoing the anatomical precision of Da Vinci’s The Muscles of the Leg (c. 1510–11), also featured in the exhibition. While male figures often exude angular strength, Raphael’s women embody softness and grace, blending anatomical accuracy with an idealized feminine beauty.

Chasing Perfection

Like Michelangelo’s David, Raphael sought an ideal even when drawing from life. In a letter to Baldassare Castiglione, he lamented the difficulty of capturing beauty: “To paint one beautiful woman I would have to see several beauties… since both good judgment and beautiful women are scarce, I make use of a certain idea that comes to mind.”

In The Three Graces, this ideal manifests in hairless, flawless skin and perfectly rounded forms. These traits align with Renaissance conventions of feminine beauty, where softness and symmetry symbolized both aesthetic and moral ideals.

Virtuous Nudity and the Male Gaze

The depiction of the Graces often embodied “virtuous nudity,” signifying truth and purity. However, nudity was also linked to shame, revealing the tension between societal expectations and artistic expression.

Historian Julia Biggs highlights how Renaissance art reflected the male gaze, with women portrayed as symbols of modesty, obedience, and maternal virtue. The Graces—Euphrosyne, Aglaea, and Thalia, daughters of Zeus—were idealized not only for their beauty but also for their embodiment of grace, a quality prized by patrons for its associations with love, balance, and harmony.

A Dual Legacy

In their Renaissance depictions, the Graces convey a patriarchal message of feminine virtue while simultaneously celebrating the female form and the camaraderie of womanhood. Their circular dance evokes the Renaissance aesthetic of balance and unity, blending ideals of grace with a quiet celebration of female solidarity.

The exhibition invites viewers to explore these intricate layers of meaning, showcasing the transformative power of the Renaissance in redefining artistic and cultural norms. Raphael’s Three Graces stands as a testament to his genius, capturing both the ideals and contradictions of his time.